Puis qu'Acre fu desheritée Et toute Surie gastée, Est nostre siecle entalanté De bonté en grant mavaisté. When Acre was despoiled And all Syria laid waste, The world longed for some good thing In the midst of great evils. ll. 29-32

Apologies for the delay. I was otherwise engaged with (finally) finishing an older project:

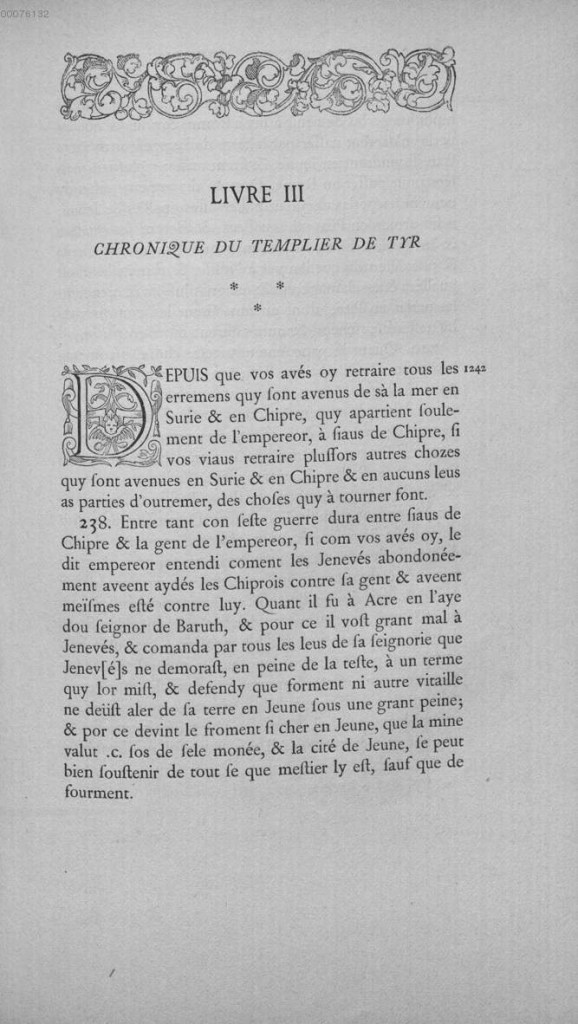

In this post we will begin our survey of texts lamenting the fall of Acre with a fun one (spoiler alert: they are all fun ones). The chronicle of the so-called Templar of Tyre was probably written in the second decade of the 14th century in an elegant Old French, more typical of courtly romances than of historiography, flavoured with some Italian. It forms the third part of the so-called Gestes des Chiprois, a history of the Crusader Kingdom of Cyprus, which survives in only one manuscript, with a turbulent history: Torino, Biblioteca Reale, Varia 433.

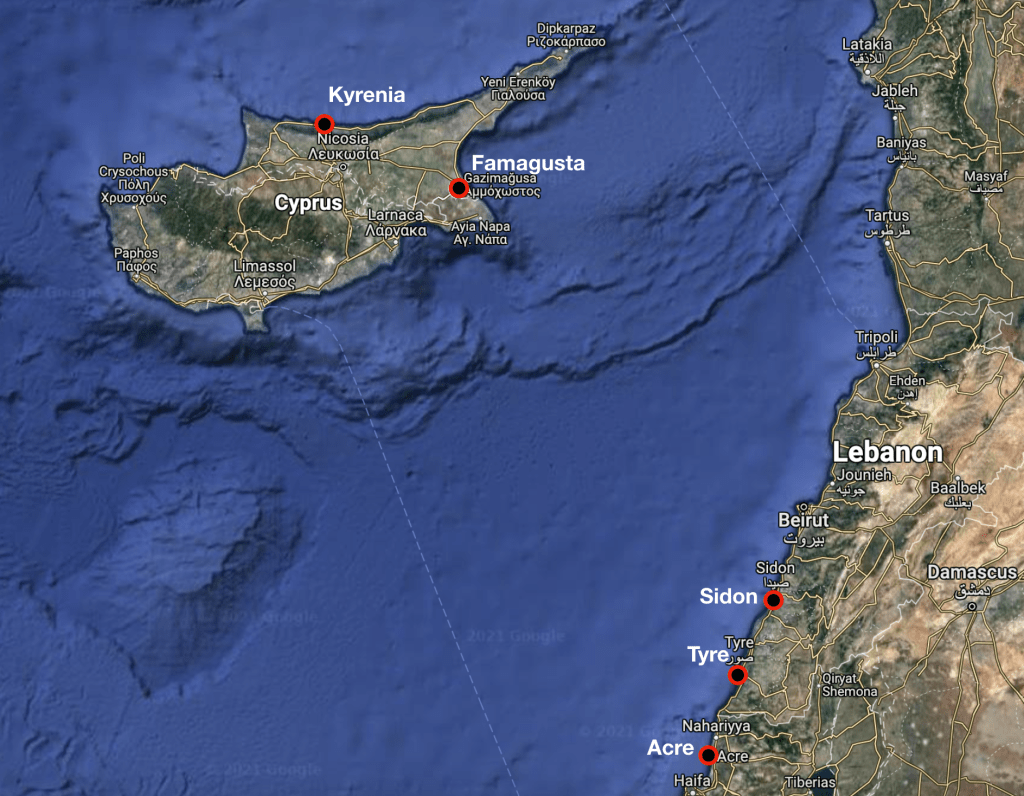

A colophone helpfully informs us that the manuscript was copied from an original in 1343 by one Jean le Miege, at the time a prisoner to Aimery de Mimars, castellan of Kyrenia Castle on Cyprus. Miege can be translated with „physician“, which is why the copyist of the Gestes is sometimes referred to as Giovanni il Medico, but it also seems to have been a common French surname at the time. The manuscript has no title, since the beginning is missing, but the 16th-century Venetian-Cypriot chronicler Florio Bustron (who is otherwise known for being the first European to write about halloumi – calumi in his Italian) in his Historia overo commentarii de Cipro referred to it as one of his sources, calling it the Gesti di Ciprioti. From here the 19th-century editors of the Gestes derived its French title.

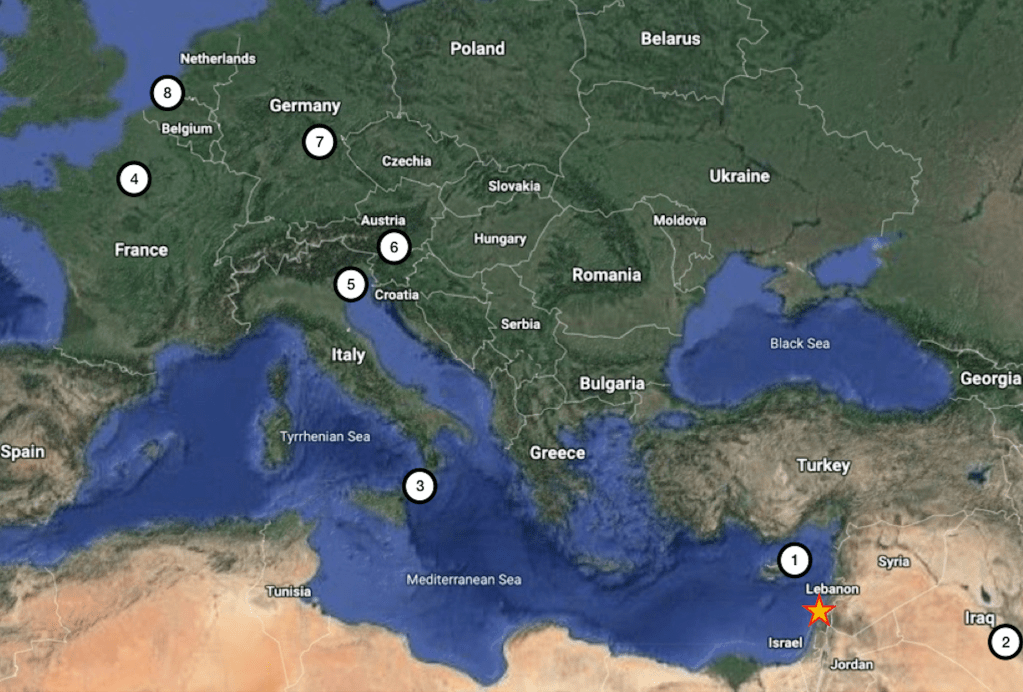

As mentioned above the one manuscript – Torino, Biblioteca Reale, Varia 433 –, in which the text survives, has a bit of a turbulent history: the copy produced by Jean le Miege in 1343 somehow found its way from Kyrenia on Cyprus to Verzuolo Castle in Piedmont, Italy. There it was found, at the bottom of an old chest, by two amateur historians, Count Massimo Mola di Larissé, who also happened to be the owner of the castle and Carlo Perrin, poking around in the castle attic. Perrin made an attempt at producing a diplomatic copy of the manuscript, but he also alerted Count Paul Riant of the Sociètè de l’Orient Latin to the manuscript’s existence. Intrigued Riant expressed interest in editing the text, but Perrin demanded to be involved in the process. As Riant seemed to have considered Perrin’s diplomatic copy sub-par, he declined. Perrin in turn declined to give the society access to the original so they had to make do with the diplomatic copy for their edition, produced by Gaston Raynaud, which was published in 1887, as did the Recueil des historiens des croisades, whose edition came out in 1906.

With Perrin’s death the manuscript disappeared and was not found again until 1979, when Alda Rossebastiano, scholar of Italian literature, stumbled across it in the Royal Library of Turin, where it ended up via the library of king Victor Emmanuel III of Savoy. But since Rossebastiano only published a small note about her find in an Italian-speaking journal on literature, it took another fifteen years until crusade historians became aware of the rediscovery of the manuscript. In 2001 Laura Minervini produced a new edition with an Italian translation (which is surprisingly difficult to come by) and in 2003 Paul Crawford translated the text into English for Routledge’s Crusade Texts in Translation series. This really opened up the text to enquiry from beyond the romance-speaking world. Most of the information here is taken from the meritorious introduction of his work.

The compiler of the Gestes has been identified as Gerard de Montreal, a Cypriot knight, who some time after 1314 (the last year to be recorded in the chronicle) and before 1321, (the year in which the Secreta Fidelium Crucis by Marino Sanudo, who made use of the Gestes as one of his sources, were presented to the pope), compiled three different texts to the Gestes as they survive in the Turin manuscript. Between them they present an account of the history of the Crusader Kingdom of Cyprus from 1143 to 1314. Earlier editors tried to establish whether or not Gerard and the Templar of Tyre are identical. While there is nothing which renders this identification impermissible, there also is nothing that would directly suggest it.

The first of the three texts of the Gestes is a collection of brief annals known as the Chronique de Terre Sainte, tracing the history of the world down to the year 1218. Since the first couple of pages are missing, it is hard to tell when the Chronique started. Internal references suggest two possibilities: either the creation of the world or the First Crusade.

The second part of the Gestes is the Estoire de la guerre des Imperiaux contre les Ibelins a highly partisan pro-Ibelin account of the so-called War of the Lombards witten by Philip of Novara

Finally, the third text is the chronicle associated with the otherwise anonymous Templar of Tyre, in which we are most interested here. The so-called Templar was – as basically all commentators since the 19th century have felt obliged to point out – not actually a Templar. For example, he was not arrested in 1308, with all other Templars of Cyprus. And while he presents a detailed account of the persecution of the Knights Templar in the following years, the events do not seem to have affected him directly and he maintains a professional distance throughout. It seems much more likely that he was a clerk or a scribe employed by the Templars, but really the only things we can say about him, we know from his own writing in his chronicle, so all the usual caveats about literary self-fictionalisation apply.

With this said, it does not seem entirely unlikely that he was born into (minor?) French-speaking nobility on Cyprus around the year 1255, served the House of Monfort based in Tyre for a significant time (c. 1269-1283), before moving to Acre and into the service of William of Beaujeu, the grand master of the Knights Templar, around 1285. The Templar of Tyre seems to have enjoyed privileged access to the grand master and also to contacts and information, e.g. the names of high-ranking spies in Cairo, capital of Mamluk Egypt. Because of this Paul Crawford speculated that the Templar of Tyre might have been some sort of „private intelligence officer“ to William of Beaujeu.

The Gestes place both the grand master and his scribe at Acre in 1290 and it is generally accepted that he was indeed an eye-witness to the events leading up to the capture of Acre by the Mamluks on May 28 1291. The main reason for this is the vividness, comprehensiveness, and accuracy of his account. Since these qualities seem noticeably diminished after the death of William of Beaujeu during the defence of Acre on May 18, Crawford suggests that the Templar of Tyre was among a small group of Templars who slipped out of the city after William’s death and made it to Sidon. Indeed, the account of those final ten days, between the death of William and the fall of the last crusader hold-out in Acre, seems much less engaged and was maybe informed by second-hand accounts after the events. After Sidon the Templar of Tyre ended up in Famagusta on Cyprus, where he probably wrote the chronicle.

The chronicle does not stop after the loss of Acre, but the capture constitutes the pivotal event of its account. In the next post here, we will take a closer look at what the Templar of Tyre has to say about the fall of Acre and how this fits into the scope of CITYFALL.