Only recently have I come across a fascinating local/regional Swiss connection to the capture of Acre in 1291, which I want to explore a bit more closely here.

I found out that there is an antepedium, i.e. a liturgical cloth used to cover an altar, at the Historical Museum of Bern (!), with French, Greek, and Latin text on it, which was probably made in Cyprus and arrived in Switzerland c. in 1291!

Why is this exciting (not that a tri-lingual Cyprian antependium is not exciting in and of itself)? Because the guy who brought it here was no other than Otto de Grandson.

Whose grandson? Well, Otto de Grandson was a knight from Grandson, in what is now northwestern Switzerland, who fought at Acre in 1291 in the service of the English king and commanded the English contingent there. He is buried in the Lausanne Cathedral (which is about 100 kms to the West of Bern).

A mesh of exciting connections began to unrol: a „Swiss“ knight, who fought in Acre and upon his return brought an artefact from the East, which was now in a museum just 10 mins away from where I work. Moreover, this knight was buried in a spectacular sculptural tomb not too far away either.

So, who was this guy, and how are he and his antependium connected to Acre and Switzerland?

Face detail of the marble effigy on Otto’s tomb in Lausanne cathedral

Otto de Grandson (of whose name a great variety of spellings abound, among them: Othon, Oton, Othes resp. Grandison) was born in c. 1238 as the oldest son of Pierre de Grandson, lord of Grandson. He lived a long and illustrous life of diplomatic service, knightly pursuits, crusading, and castle-building, well worth of a novel or indeed a series of novels. The stations of his life connect his tiny corner of modern-day Switzerland to England, in particular the royal court at London, and parts of Wales, to the French royal court at Paris, to Gascony and to Flanders, to Italy, the Roman Curia in Rome and Orvieto, also to Sicily, and, finally to Cyprus, Armenia, and, well Acre and the Holy land.

But his long and eventful life started where it would also come to a conclusion, when he died probably well in his 80s in 1338: in Grandson, a small fief with an impressive castle about 25 kms north of Lausanne, on the southwesternmost tip of Lake Neuchâtel. In the 10th and 11th century Grandson, situated in the very northwest of modern-day Switzerland, had been part of the Kingdom of Burgundy. Around 1300, it was part of the Barony of Vaud, which was in turn a semi-independent part of the County of Savoy. Savoy was a small but influential polity, with its centre in northwestern Italy. But because it controlled the western alpine passes, which connected the ancient, cosmopolitian, and rich Mediterranean world to the increasingly commercialised and prosperous world of Northwestern Europe, the counts of Savoy were politically and economically punching way above their weight. In 1313 count Amadeus V achieved the status of imperial immediacy („Reichsunmittelbarkeit“) from Emperor Henry VII.

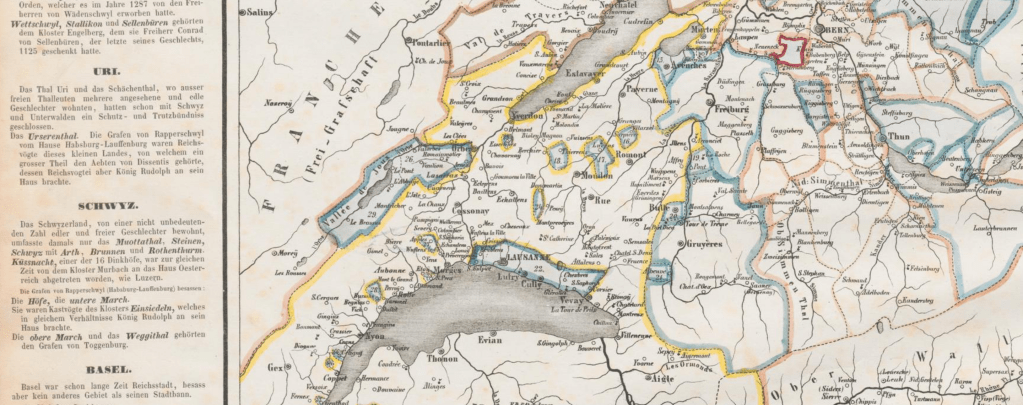

The western part of what is now Switzerland c. 1300

Otto became to be the most prominent of the so-called Savoyard knights, a group of knights from Savoy, who, in the 13th and early 14th century, went to serve the king of England (the topic of the Savoyards in 13th-century England is an endlessly fascinating one, and you can read a more comprehensive and highly informative piece by Christopher Tyerman about it here).

Some background on the English-Savoyard connection: in 1236 King Henry III of England had married Eleanor of Provence, who had strong family ties to the counts of Savoy. When she moved to London, she brought with her a large Queen’s party of uncles and cousins, know as the „Savoyards“, who were given influential positions at the English court. Oredictably, this earned them the enmity of the Londoners and the English barons. Most prominent among the Savoyards was Eleanor’s uncle William of Savoy, Bishop of Valence, who would become one of the closest advisors of her husband, the English king.

This marked the beginning of a close relationship between the English monarchy and the County of Savoy. The young son of the lord of Grandon, Otto, would make is way to England, in order to serve King Henry III in the 1250s. At the time he would have been between 14 and 18 years old. It is likely that he served in the royal household of Henry’s son and heir Prince Edward (later King Edward I aka „Longshanks“, Hammer of the Scots, of dubious Braveheart fame) during the battles of Lewes (1264) and Evesham (1265) of the Second Barons‘ War against the English barons led by Simon de Montfort. After the death of Simon and the decisive defeat of the barons at Evesham, Otto was awarded by Prince Edward with properties close to London .

Simon of Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, and, for a time, de facto ruler of England, as depicted in a stained glass window in Chartres Cathedral

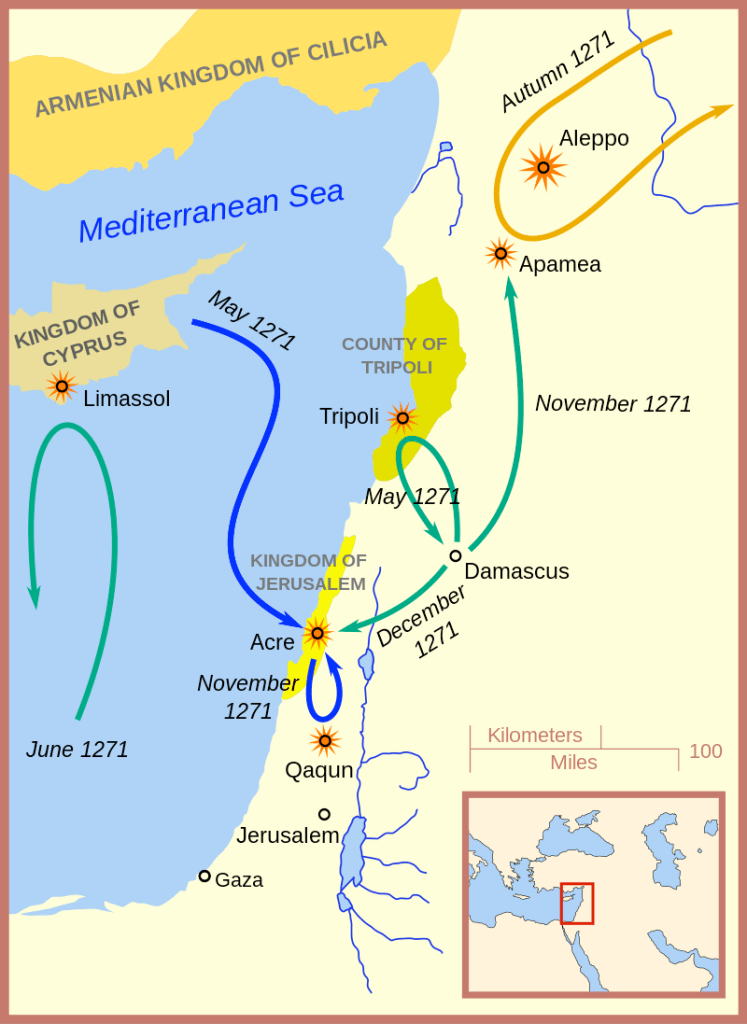

In 1271, after Otto had been knighted together with prince Edward, he joined Edward on his crusade to the Holy land (an endeavour sometimes termed the 9th crusade). It can also, maybe more sensibly, be seen as a delayed part of the 1270-crusade of the French King Louis IX, who had landed in Tunis with his army, only to die there from disease shortly after his arrival. When Edward and Otto arrived in Tunis much-delayed to join the French king, he was already dead, and the treaty that had been signed between the crusaders and the Muslims, obliged the Christian lords to not attack Tunis anymore. After withdrawing to Sicily and considering their next steps for some time, Edward and his crusaders sailed East, were they arrived in Acre on 9 May 1271 with eight sailing ships and a thirty galleys.

It can be assumed that Otto took part in most of the (limited) military action that followed: raids and skirmishes with Bairbars‚ Mamluks, which were at the time harassing what remained of the Crusader states on the Eastern Mediterranean littoral. In the end the fighting did not amount to much, except maybe to keep the Mamluks away from Acre. At least for the time being. But regarding Otto there is one particularly striking episode from that time, transmitted by the Flemish chronicler John of Ypres, who wrote his Chronicon not long after Otto’s death in 1338:

„I have heard the following story from the lips of certain honourable and trustworthy men of Savoy, who, however, told me not of what they had seen but of what they had heard. Now these men alleged that once upon a time there was in Savoy a certain lord of Grandson, whose wife bore him a son. When the astronomers were summoned to examine, calculate, and decide the child’s nativity, they declared that if he grew to manhood, he would be great, powerful, and victorious. There was also present on this occasion a person full of superstition, or shall I rather say of divine inspiration, who taking a brand from the hearth declared that the boy would live only so long as the brand lasted, and that he might live the longer thereupon had the brand built up in a wall. The boy lived, grew to manhood, and to old age, with ever increasing honour; until at last, weary of life through burden of his years, he ordered the brand to be taken out of the wall and cast into the fire. Hardly was the brand consumed, ere the good knight expired. My informants told me further that this fateful lord of Grandson was beyond sea in the company of the son of the King of England; and that when he heard how the prince had been poisoned, alone, trusting, as I suppose, in the fate that had been foretold for him, dared to suck the venom from the wound; and thus through his aid was Edward healed. Afterwards this lord of Grandson and his kinsfolk rose to high with the Kings of England, and unto this day have great repute in that country. But of this can I avouch more than was told to me.“ (trans. by Girart Dorens 1909)

An almost fairy-tale-styled literary image emerges of Otto Grandson as a man whose life was pre-ordained by prophecy and vouchsafed by miraculous circumstances. A man who, thanks to these circumstances, was able to control the conditions of his own life, and even determine the hour of his own death, a awe-inspiring and also slightly unnerving quality to medieval readers.

Almost twenty years later, after many more years of distinguished service for Edward, now King of England, Otto would return to the Holy land to play an important part in the final battle for Acre in 1291. I am going to explore this in a second post soon, so watch this space.